“Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun…” Robert Frost, Mending Wall

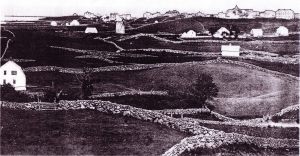

Stone walls in Block Island, Rhode Island, c. 1880. Block Island Historical Society, printed by Robert Downie

Frost, deep frozen ground, not poets, is not the only nemesis of the old stone walls crisscrossing this island and all the rest of New England, but it is a formidable one. At the peak of their domination of the landscape in the mid 1800’s, there were an estimated 240,000 miles of them. The total weight of them equaled sixty Pyramids of Giza or about four hundred million tons[i]. One by one, the farmers gathered the stones and built the walls.

The other (Robert) Frost wrote famously in his poem, Mending Wall, “Good fences make good neighbors.” New England soil and geology scattered the material for these borders across this landscape in forests and fields. The frost does not just undermine existing walls, the frozen earth provided for them. Each winter and spring cycle the frost slowly worked up millions of rocks through the soil to the surface. Farmers cultivating the land and before them farmers raising Merino sheep each year faced one of their most arduous tasks: picking up the stones, called “two handers,” throwing them first into a formidable pile, then carting them to build the walls. Walls to keep in livestock and keep out someone else’s livestock; walls to delineate property; walls to get the rocks out of the way of plows and the grazing of cows and sheep.

Farmers and estate owners often planted Sycamore maples and pin oaks and Norway maples and sugar maples and American beech trees along these walls for shade, maple syrup, further definition of who owns what land, and because they are beautiful. They assumed residence beside the wall for decades or a century. The relationship between the wall and the tree is eventually contentious. Trees grow, albeit slowly, but inexorably. Up and out and thick in the trunk. And not just stems and buds, flowers, and leaves. The girth of the trunk expands in the cambium, that thin layer of vascular cells between the inner tree and the outer bark, between the xylem and the phloem. The xylem presses inward eventually hardening into heart and sapwood. The phloem presses outward creating the vessels that become cork like and harden into bark. One cell at a time, the cambium does its work. Mitosis, dividing, each tiny increment insignificant, but relentlessly they push out and up. The annual growth cycle of early wood and late wood creates the rings that chronicle the age of the tree and the history of the weather each year.

maples and American beech trees along these walls for shade, maple syrup, further definition of who owns what land, and because they are beautiful. They assumed residence beside the wall for decades or a century. The relationship between the wall and the tree is eventually contentious. Trees grow, albeit slowly, but inexorably. Up and out and thick in the trunk. And not just stems and buds, flowers, and leaves. The girth of the trunk expands in the cambium, that thin layer of vascular cells between the inner tree and the outer bark, between the xylem and the phloem. The xylem presses inward eventually hardening into heart and sapwood. The phloem presses outward creating the vessels that become cork like and harden into bark. One cell at a time, the cambium does its work. Mitosis, dividing, each tiny increment insignificant, but relentlessly they push out and up. The annual growth cycle of early wood and late wood creates the rings that chronicle the age of the tree and the history of the weather each year.

The power of this tiny expansion continues unabated. A fraction of an inch at a time, it does not stop. When the tree necessarily grows in diameter, a stone wall in its path suffers a slow demise. Eventually a bulge becomes a fall becomes a collapsed hole. The wall begins its slow dis-integration back into the soil that spawned it. The fields they once defined sometimes revert to wall-demised overgrown forests once again.

“When a friend calls to me from the road

And slows his horse to a meaning walk,

I don’t stand still and look around

On all the hills I haven’t hoed,

And shout from where I am, What is it?

No, not as there is a time to talk.

I thrust my hoe in the mellow ground,

Blade-end up and five feet tall,

And plod: I go up to the stone wall

For a friendly visit.” Robert Frost, A Time to Talk

In 1961, Dr. Stewart Wolf, the head of medicine at the University of Oklahoma, met a local doctor for Roseta, Pennsylvania, who told him about the remarkable, negligible rate of heart attacks from 1954 to 1961 in Roseta[ii]. Curious, Dr. Wolf confirmed the anecdotal evidence by researching death certificates for the town during that period. Numerous studies followed, including a fifty year exhaustive one comparing Roseta to the similar sized town nearby, Bangor, PA, as natural experiment control. The researchers named these findings the “Roseta Effect.” Why they were so different in heart attack frequency was the pressing question.

Researchers concluded that the community cohesion of the Italian culture and unity centered on the united worship in the church, common agreed upon values, and closely shared family and community lives there lowered the stress level, loneliness, and attendant health risks. People still died, of course, but later, and not of heart attacks. Normally at risk men from 54 to 64 had almost no heart attacks. They did not eat the Mediterranean diet but regularly chowed down on sausage fried in bacon grease; they smoked unfiltered tobacco, and worked extremely hard in slate mines, contracting the usual toxic dust related diseases. But they did not drop dead from heart attacks.

They were hardworking, poor, lived in tightly packed similar housing, and did not contend with social envy or material or pretentious aspirations. Simple, deep shared faith as a given, mutually supportive lives connected everyday face to face with close friends and relatives. Loneliness was foreign to them. You can read more in the footnote link.

As the years merged into decades, the trust, social cohesion, security, and friendships of 1950’s Roseta slowly effervesced like flat soda. Roseta became homogeneous with the rest of the country. People died, moved way, families broken and dispersed, neighborhoods broken and dispersed, the world seen filtered through the lens of a screen, the mines closed, new folks moved in. The heart attack rate grew until it was indistinguishable from the rest of us. Roseta became modern, and the Roseta Effect dissipated like the morning mist.

Like the inexorable growth of tree trunks first strained, then broke down centuries of stone walls, inexorable modernity broke down the societal boundaries of Roseta. In Part II, while we cannot regress into an idyl of nostalgia, we can do a few good things to find our way home. Until next time.

“The postmodern vision of society, in rejecting objective truth and inherited cultural bonds, has dissolved the very idea of community. In place of solidarity, it offers only a marketplace of transient identities, each competing for recognition while eroding the deeper structures—family, faith, and nation—that once made society coherent.” Roger Scruton, The West and the Rest

[i] Article from AtlasObscura.com

[ii] I learned about this story as part of a great Sunday homily our pastor, Father David Thurber, taught us. Curious, with just a quick Google search, the “Roseta Effect” story had many related scientific studies.

Not only in Roseta, Jack. But a very happy lady lives on.100-year-old Witney woman says ‘happy family’ is key to long life

| | | | | |

|

| | | | 100-year-old Witney woman says ‘happy family’ is key to long life

Dorothy Howard celebrated her 100th birthday surrounded by family and friends in Witney. |

|

|

R/Denis

LikeLike

Faith and reason. How did these two faculties ever get put together? When the Greeks entered the Church way back in the first century… the “apologists”. Big mistake. Jesus said, “My kingdom is not of this world.” This is what gives it it’s awesomeness. “We preach Christ crucified… to the Jews a stumbling block… to the Greeks foolishness. However, to those who are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God“

LikeLike