It appeared to me that there were two ways of arriving at the truth. I decided to follow them both” Father George Lemaître (from a NYT’s interview[i])

Father George Lemaître’s “Big Bang” theory predicted a cosmic whisper proven to exist a few decades later, a Cosmic Microwave Background radiation that changed our model of how the universe came to be.

Within us all is another sort of whisper that is analogous to the cosmic whisper that points to creation. An uneasiness, an anxiety that we may deny, ignore if possible, and it is unique to human beings, unknown to other animals as far as we know. We work hard to distract ourselves from it. Linked to self-awareness and foreknowledge of our own mortality, there are three certainties that buzz in the background of our existence. Our mortality – finitude as biological life, our contingency every moment of every day, and the nagging unavoidable question that something greater than and outside of ourselves exists and resists understanding.

This inner voice is incessant, yet just a whisper most often overwhelmed by our favorite loud distractions, diversions, entertainments, screens, busyness, and noise either discordant or pleasant. When on those rare occasions we pay heed to Blaise Pascal’s warning and spend an hour alone in a room by ourselves in silence, the whisper comes a calling, and it is a gentle murmur, the faint echo of the hole in our hearts.

All of us have sensed the soft insistent voice as a disquieting – a background restlessness. Many have defined it from different perspectives. Philosophers and psychologists, saints[ii] and sinners, and the incredulous and the curious have wondered at this unease, this whisper. The nineteenth and twentieth century produced many minds who sought to understand it. Georg Hegel, Søren Kierkegaard, Carl Jung, Edmund Hurrserl, Martin Heidegger, Edith Stein[iii] and many others speculated about the source of this Anxiety, this hum, this unavoidable “inquietem” when the finite encounters the infinite. Most of us, too, have our own evasions or explanations through philosophy, psychology, or some spiritual path.

“Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood….” The Road Not Taken, Robert Frost

Since the topic is unwieldy, and I’m trying to write about it, I get to define the borders of the inquiry. All complaints about half-baked abridgement and sophomoric errors, please direct them to the author or editor with kindness and look past the gaps in the landscape.

Edmund Husserl was the creator of a branch study of philosophy he named phenomenology. He was troubled that philosophy (and science too) had accrued so many abstractions, theories, and inherited concepts that obscured the raw experience of things. He conceived phenomenology to attempt to bracket assumptions and preconceptions to recognize “the things themselves” (zu den Sachen selbst!). In “The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology,” he wrote, “The exclusiveness with which the total worldview of modern man let itself be determined by the positive sciences and blinded itself to all the questions which are decisive for a genuine humanity signifies an indifferent turning-away from the questions which are decisive for a genuine humanity. Merely fact-minded sciences make merely fact-minded people.” When we use and value terms like “authenticity” or “intentionality” or “lived experience,” the soil in which those ideas developed were phenomenology, and Edmund Husserl planted the seeds. His influence on the twentieth century and subsequent streams of thought cannot be overstated.

As it happens, what starts as speculation in the faculty lounge, a century later diffuses through to social media and common understanding. Ideas do indeed have consequences, oftentimes unintended.[iv]

“There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” William Shakespeare’s Hamlet (Act 1, Scene 5).

To keep things tightly abridged, we’ll limit this inquiry to two of Husserl’s most brilliant students, Martin Heiddeger and Edith Stein, who contrast in their conclusions and their lives. They illustrate two of the three prevalent responses to the whispered, insistent invitation. The third, and most common, we experience every day on our screens. Postmodern people put whispers on ignore, and we are all often complicit. Politics, sports, celebrities, “death scrolling,” entertainment, convincing ourselves that our frantic busy-ness is urgent are among our devices of avoidance. This response works effectively for most of us most of the time. For a while.

Take a brief excursion with me to examine the other two paths followed by Husserl’s prize pupils who acknowledge what we hear in silence. Stein was Husserl’s research assistant (1916–1918), and Heidegger was Husserl’s star student who eventually succeeded him as professor. Stein and Heidegger met through their shared connection to Husserl. While not close coworkers, they were part of the same phenomenological school. Both believed the scientific and cultural inclinations for abstraction endangered the meaning of our direct perceptions unbracketed by preconceptions. Each acknowledged some form of the whispers but were sharply divergent in their answer.

Heidegger named ‘Angst’ as our unspecific fear of being finite in an inescapable abyss and inherent in ‘Dasein,’ our personal experience of human existence. Angst is the unease that grips us when the everyday meanings of life fall away and we face the raw fact that we exist — alone, free, and finite. Heidegger’s proposed response to nothingness is authenticity. Face the great emptiness honestly. Don’t flee into distractions or comforting illusions. Let Angst strip away false securities so you see life as it really is — fragile and contingent. Accept our finitude and that we are “being-toward-death.” Our mortality gives us urgency and depth to existence. Live it with lucid courage. Live deliberately, aware that our choices define who we are in the face of the void.[v] From this and Nietzsche’s ‘will-to-power’ emerged our culture of celebrity worship, self-obsession, and self-invention in all its manifestations like a slime creature from the bog.

“Angst reveals in Dasein its being toward its own most potentiality-for-being—that is, being-free for the freedom of choosing itself and taking hold of itself.” [vi] In a slightly updated synopsis, “Suck it up, buttercup!”

Edith Stein thought that Heidegger was vivid and right in “Being and Time” as far as he went, and he succeeded in defining our existence as finite, temporal, and oriented toward death. But she thought he was incomplete. She acknowledged the whispers but knew we needed something beyond our inadequate self to reply to them.

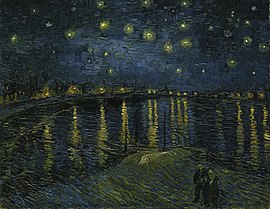

Without transcendence, Heidegger’s descriptions of human existence are truncated. Stein believed this leaves a “half-truth”: man is finite but as a person is also open to the infinite. For her, his analysis ends “at the gate of eternity,” but refuses to step through. Each human being is an irreducible person with individuality, vocation, and the capacity for communion with God. Where Heidegger stresses “being-towards-death,” Stein perceives being called to life eternal. Where Stein saw what Augustine wrote in his ‘Confessions’ about the longing and hole in the human heart, Heidegger saw only the hole, and his solution was insufficient. His was a work of great force, but in the end it left the reader in darkness. The soul longs for light, and he shows us only the night.

Their lives could not have ended more differently. Heidegger followed the logic of his convictions and became enamored himself of the German Volk and eventually with its leader. He never repudiated his involvement with the National Socialist movement in Germany. He became the Rector of Freiburg University and in his notorious “Rectoral Address,” he said these things, again with a bit of Nietzschean influence: “The spiritual mission of the German people is to find and preserve its truth in its fate.” And “The Führer himself and he alone is the present and future German reality and its law.” Not much else needs to be added to that.

Stein’s conversion from atheism was a miracle story. She read St. Teresa of Avila’s autobiography, and a light came on within her. “This is the truth,” she marveled. Edith Stein did nothing halfway. She became first a Catholic, then a professed Carmelite nun. She fell in love with her Creator. In April of 1933, she wrote to Pope Pius XI about the rise of Nazism. “For weeks we have seen deeds perpetrated in Germany which mock any sense of justice and humanity, not to mention love of neighbor. … As a child of the Jewish people who, by the grace of God, for the past eleven years has also been a child of the Catholic Church, I dare to speak to the Father of Christendom about that which oppresses millions of Germans…. Everything that happened and continues to happen daily comes from a government that calls itself ‘Christian.’ … The responsibility must fall, also, on those who brought this government to power and still seek to justify it. I am convinced that this is a general disaster for humanity.” Historians believe her letter influenced the pope’s encyclical in 1937, Mit brennender Sorge (With burning Concern), which condemned Nazi racism. Later, to her prioress she said, “I understood the cross as the destiny of God’s people, which was beginning to be laid upon them then.”[vii]

first a Catholic, then a professed Carmelite nun. She fell in love with her Creator. In April of 1933, she wrote to Pope Pius XI about the rise of Nazism. “For weeks we have seen deeds perpetrated in Germany which mock any sense of justice and humanity, not to mention love of neighbor. … As a child of the Jewish people who, by the grace of God, for the past eleven years has also been a child of the Catholic Church, I dare to speak to the Father of Christendom about that which oppresses millions of Germans…. Everything that happened and continues to happen daily comes from a government that calls itself ‘Christian.’ … The responsibility must fall, also, on those who brought this government to power and still seek to justify it. I am convinced that this is a general disaster for humanity.” Historians believe her letter influenced the pope’s encyclical in 1937, Mit brennender Sorge (With burning Concern), which condemned Nazi racism. Later, to her prioress she said, “I understood the cross as the destiny of God’s people, which was beginning to be laid upon them then.”[vii]

Heidegger died in bed of an infection at eighty six in 1976. St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross (Edith Stein) was murdered in 1942, gassed in a Nazi gas chamber at Auschwitz together with her sister, Rose, who also became a Carmelite. St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross was canonized as a Catholic martyr on October 11, 1998, by St. Pope John Paul II in St. Peter’s Square in Vatican City.

“It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.” Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince (1943)

“Begin now to be what you will be hereafter,” wrote St. Jerome. He encapsulates what it means to hear the whispers, and like St. Augustine who understood that we were made for union with our Creator, Jerome knew it begins here and now. St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross knew that a life without listening and responding to the whispers of God was a life truncated, a half-life, a life that falls short of what it could be, what it is intended to be. Or as St. Irenaeus wrote in the second century, “The glory of God is man fully alive.”

Each of us in moments of reflection knows that we are called and created to be something more than randomly evolved ambulatory meat destined only for annihilation. Heeding the whispers is how we begin. “Lord, I believe. Help my unbelief.”

“I fled Him, down the nights and down the days;

I fled Him, down the arches of the years;

I fled Him, down the labyrinthine ways

Of my own mind; and in the midst of tears

I hid from Him, and under running laughter.” “Hound of Heaven” Francis Thompson

[i] Duncan Aikman, “Lemaître Follows Two Paths to Truth,” The New York Times, February 19, 1933, p. 3.

Shareable reproduced copy available via the Vatican Observatory archives: Lemaître Follows Two Paths to Truth (PDF)

[ii] One of the earliest commentators on record is St. Augustine. In his Confessions, he wrote about this undeniable underlying whisper, which he understood as a hole in our heart as creatures made in Imago Dei. His most famous and oft used quote spoke of it. He recognized this unease when the finite confronts the infinite. “Oh God, You made us for Yourself and our heart is restless until it rests in You.”

[iii] Since there are more than a few professors who occasionally read this and a couple who teach philosophy at good universities, I won’t embarrass myself by pretending to know a lot more than I do about the details and texts of these great minds.

[iv] A seminal book for me a few decades back was Richard Weaver’s “Ideas Have Consequences.” Written in 1948, I still recommend it to your attention. The line can be followed from Husserl either as an extension of or in opposition to his work as varied as the Existentialism of Satre, the Absurdist resignation and nobility of Camus, and the personalism of St. John Paul II. Nietzsche, Descartes, Hume, Foucault, so many others have contributed to and formed the radical “culture of self-invention” that so amplifies and distorts our understanding of human longing in these post Christian times. All of this is well beyond the scope of these humble musings.

[v]An echo of Nietzsche’s ‘will to power’ in this and a foretaste of our culture of self-invention.

[vi] Being and Time”, Martin Heidegger, 1927

[vii] Heidegger and St Teresa Benedicta of the Cross illustrations from two articles. Heidegger from https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/31/books/heideggers-notebooks-renew-focus-on-anti-semitism.html

St Teresa from https://www.ncregister.com/blog/edith-stein-this-is-the-truth

The relationship between music and mathematics and the universe is mysterious. We can start with an ancient theory and wander around a bit. Bear with me, and we’ll see where this goes.

The relationship between music and mathematics and the universe is mysterious. We can start with an ancient theory and wander around a bit. Bear with me, and we’ll see where this goes. Music, too like math, is a wonderous alchemy of human cognition and the universe. In a sense, the universe only exists because someone is there to perceive it. Human creativity and genius took the stuff of the universe – wood, metal, reeds, strings, felt hammers, and more – fashioned and refined and tuned a vast diversity of instruments which enhanced and added complexity to the marvel of human voice and created sound images that reflect our universe with inexhaustible variety.

Music, too like math, is a wonderous alchemy of human cognition and the universe. In a sense, the universe only exists because someone is there to perceive it. Human creativity and genius took the stuff of the universe – wood, metal, reeds, strings, felt hammers, and more – fashioned and refined and tuned a vast diversity of instruments which enhanced and added complexity to the marvel of human voice and created sound images that reflect our universe with inexhaustible variety. The human person has a curious capacity for wonder. The universe is filled with persistent, unexplainable beauty, but why are we capable of noticing and being awestruck by this chain of astonishment? Chaotic, yet ordered; incomprehensible, yet intelligible, we seem to be created, our brains seemingly wired to appreciate it all. How marvelous is our capacity to wonder and to be in wonder. To be amazed and deeply longing simultaneously for a fulfillment unknown. Why is this so?

The human person has a curious capacity for wonder. The universe is filled with persistent, unexplainable beauty, but why are we capable of noticing and being awestruck by this chain of astonishment? Chaotic, yet ordered; incomprehensible, yet intelligible, we seem to be created, our brains seemingly wired to appreciate it all. How marvelous is our capacity to wonder and to be in wonder. To be amazed and deeply longing simultaneously for a fulfillment unknown. Why is this so?