“Play is often talked about as if it were a relief from serious learning. But for children, play is serious learning. Play is really the work of childhood.” (Mr.) Fred Rogers

When we lived in Farmington, Maine, happily we were parishioners in the wood framed, off the main street, St. Joseph Church. Sunday after Mass, we often helped with a coffee and snacks gathering in the basement church hall across the street. As well as a venue for parishioners to share stories and freshen friendships, newcomers could meet the regulars and ask questions about the parish, the town, and be welcomed into friendly fellowship. Everything from where the town dump was and good sources for the best local plumbers and electricians as they made unwelcome discoveries about their new house to how many children do you have and where do you work.

For the kids, though, there were different priorities that took over right after the weekly cookie and donut raid. Our son, Gabe, and his two platoon members, Jason, and Paul, all about ten years old, immediately went looking for the toy bin under the stairs for their weekly games, then having secured what they needed, bolted outside to get sweaty and dirty for the ride home. If we were lucky, their church clothes survived for another week with just a little stain remover. One late summer Sunday morning, we were conversing with two folks new to Franklin County, both of whom had moved to town to teach at the Farmington campus of the University of Maine.

The conversation, as conversations with new acquaintances of an academic bent sometimes go until we get to know one another, was a bit formal with some careful probes to establish the guidelines and borders. It was quite clear quite early that our newly welcomed folks were unlikely to be National Rifle Association members or deer hunters. Having never lived in a rural area or in truth very far away from an academic enclave, they carefully shared some concerns about the local folks who weren’t members of the university. Did they hunt? Did they wander around unsupervised and armed on to other people’s land?

I was trying to reassure them that most hunters I knew were respectful of other people’s property, responsible, careful, and skilled. The native-born Maine residents that we had come to know, trust, and love could be counted on for affable conversation, a devastating creative dry wit, advice both practical and theoretical, and in an emergency, they were self-sufficient, resolute, calm, and completely reliable. They just needed some venison in their freezer. Deer, as well as pastoral, beautiful, fast, doe eyed, and all the rest of Bambi lore, were ambulant meat after all. Since the predators were mostly gone, if the herd was not controlled, the deer would first strip the young trees of any bark they could reach and then starve in the winter. Our conversation partners discreetly exchanged skeptical looks. Maybe deer birth control would be a better method? Condoms were a problem, I suggested. The bucks hated them and could not be trusted to use them consistently. Doe were notorious for forgetting to take their pill. But I digress.

Suddenly, as enthusiastic boys are inclined to do, Gabe, Jason and Paul burst into the conversation with an urgent and deadly serious interruption. “Dad, Dad, the door to the closet is locked! We need the church guns!”

I think our new friends returned the next week, but my memory is fuzzy after so many years.

“The Pope? How many divisions does he have?” Joseph Stalin

The Russian tyrant and “Man of Steel” was right of course.[1] But more right was St. Pope John Paul II.[2] He knew the military might of the Soviet Union could not be resisted, but his battle could be waged by spiritual and cultural weapons. Karol Wojtyla understood that culture was the most dynamic force in world history, and it was there he and the Holy Spirit could prevail.

The man who would become pope and saint grew up in the most difficult of times. After the Warsaw Pact, his beloved Poland was invaded from the east and west and divided by agreement between two of history’s most ruthless tyrants: Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin. After Hitler broke the agreement by invading Russia, Poland was brutally ruled by the Nazis. Hundreds of thousands of Poles were murdered, including twenty percent of its Catholic priests along with many of its writers, poets, artists, academics, and intellectuals. Both Nazis and Communists crushed any resistance by trying to destroy its culture. In the Eastern sector before Hitler broke his word, and not to be outdone, the notorious Russian secret police NKVD murdered 22,000 Polish officers and intelligentsia in the Katlyn woods — one at a time with a bullet in the back of the head in April and May of 1940. However, the Polish culture was deeply embedded in the hearts of its people after a thousand years of Catholic thought, writings, art, theater, and poetry memorized as children. Obliterating it proved to be a thorny thicket for both the Reds and the Nazis.

Young Karol Wojtyla was part of a widespread secret resistance, but his part was non-violent. His group frequently held clandestine performances and readings of Polish literature, poetry, and plays to pass on tradition and help the strong Polish culture to endure. When the Church was harshly suppressed, he heard the call to the priesthood and secretly entered the underground seminary of Cardinal Sapieha. Father Wojtyla was ordained on the Feast of All Saints in 1946.

Towards the end of the war at the Malta Conference, the allies on the brink of defeating the Third Reich met to decide the fate of Eastern Europe. The Poles had no place at that table; they were divvied up like the garments of Jesus. To placate their former ally, Joseph Stalin, Great Britain, the United States, and other allies agreed that many of the former independent states like Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, East Germany, and Estonia would remain under the domination of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) behind the Iron Curtain as Churchill explained. Poland mourned that in World War II their beautiful country lost twice. One oppressive and murderous regime was replaced by another.

The Soviets destroyed churches and church schools, making them warehouses or vacant lots, persistently suppressing the authority of the Church. Many Catholic clergy were exiled to Siberia. The puppet government installed an Orwellian system of secret police, informers, and a formidable propaganda machine. Schools were taken over to indoctrinate the children into Communism starting in kindergarten. Soviets deliberately set up social and work structures to undermine family life with small mandatory apartments and staggered shifts to make family dinners less likely. The children ultimately belonged to the state. The Church and the family are where culture is sustained, and they were recognized as the greatest impediment to full implementation of the Communist Marxist ideology.

Throughout his early priesthood, Father Wojtyla organized young people, especially couples and through camping and ski trips into the Polish hills and canoeing on its rivers. Mass was celebrated on the altar of an overturned canoe. His focus from the start was to imbue and sustain Polish culture and most importantly its faith in the hearts of its people, always emphasizing the innate freedom and dignity of each individual person as created Imago Dei. He taught and discussed around the campfire that human rights were not conferred, nor could they be destroyed, by the state. He was regarded by the Communists as a thinker, not a doer, and was to some degree left alone as not dangerous to the regime, which allowed him without protest to become first an Auxiliary Bishop then Archbishop and Cardinal of Krakow. They permitted him to attend all the Vatican II meetings from 1962 to 1965, and he wrote the bulk of one of its most significant documents, Gaudium et Spes (Joy and Hope.)[3]

But the Communists soon learned of his resolve during the prolonged battle from 1967 to 1977 over Nowa Huta (New Steelworks)[4], their planned “worker’s paradise” and factory community outside of Warsaw. Communist planning omitted the construction of any church. No need for the old superstitions in the paradise of the worker. Archbishop Wojtyla fought for years to disabuse them of their illusions that such a thing could pass on his watch.

I remember the pictures of the Ark of the Lord Church in Life Magazine when it was finally built. Prior to its construction, Mass was celebrated in all weather in a large field with a resilient large steel cross dug into the earth from the very beginning of the “worker’s paradise.” The world began to take note of this handsome and forceful leader with the theater trained voice who preached non-violent resistance and the dignity and innate freedom of Polish men and women. He was unrelenting.

When the world was surprised in 1978 by his elevation to the papacy as Pope John Paul II, the first non- Italian in four and a half centuries, the Politburo started to understand fully the worst mistake of its sixty-year history of brutal rule. When he was elected Pope, he immediately announced that “the Church of Eastern Europe was no longer a Church of silence because now it speaks with my voice.”

Italian in four and a half centuries, the Politburo started to understand fully the worst mistake of its sixty-year history of brutal rule. When he was elected Pope, he immediately announced that “the Church of Eastern Europe was no longer a Church of silence because now it speaks with my voice.”

“Open wide the doors for Christ. Do not be afraid.” His first homily as Pope spoke directly to the people and as a challenge to Communists everywhere.

In 1979 he made his first visit as Pope to his homeland. The impact was world changing. In Poland, the regime had fostered isolation and distrust, so no one knew how many were dissatisfied outside of their immediate circle of trusted friends, and how many mourned the suppression of their ten centuries deep Catholic culture and longed for its freedom and sanctuary. All feared exposing their hatred of the tyrant because informers were everywhere, and dissent earned you a long cold train ride to Siberia. If you were lucky. When Pope John Paul came and spoke tirelessly – fifty talks and homilies in nine days, celebrated numerous Masses, and led them in many prayers of hope, many witnessed after that visit for the first time they felt safe, accepted, and united. And there were millions of them.

In Victory Square in Krakow, hundreds of thousands of people chanted and sang, “We want God. We are Your people. He is our King. He is our Lord!” John Paul put his hand on his heart and wept quietly.

He spoke and it was the turning point, the first domino to the fall of the Soviet Union. “And I cry. I who am a son of the land of Poland and who am also Pope John Paul II. I cry from the depths of this millennium. I cry on the vigil of Pentecost. Let your Spirit descend! Let your Spirit descend and renew the face of the earth, the face of this land. Amen.”

He never spoke once in fifty talks of those nine days about government or ideology or economics. His challenge was individual and human, one heart and mind at a time. He simply told them in essence, “You are not who they say you are. You are a Christian people united in faith and freedom and culture.” His often-quoted favorite scripture was from the Gospel of John, “The truth will set you free!”

He instilled hope in a non-violent ‘revolution of conscience.’ He called himself the Slavic Pope signaling he was speaking not just to Polish people but to all the enslaved people of Eastern Europe.

In 1980, the Solidarity union was formed in the Gdansk shipyards and led by electrician Lech Walesa as a direct reaction to the Pope’s rallying cry. He led a strike that almost overnight became national for grievances against the workers by the state. When the government eventually offered new benefits, freedoms, and fair treatment for the Solidarity workers in the shipyards who were barricaded in their warehouse, Walesa refused until the offer was extended to all the workers in Poland. Twenty thousand people gathered around the besieged warehouse in support. The government folded, and for the first time a Communist government acquiesced in the just demands of workers. All the workers.

For the next ten years, the unrest spread throughout Eastern Europe. The fire of hope and the truth about the nature of human beings was ignited and could not be extinguished by force or lies. A severe martial law was imposed in Poland. The pressure on the government went underground but persisted. Pope John Paull visited again 1983, 1987, 1991 (twice), 1995, 1997, 1999, and 2002. When Ronald Reagan saw the video of the Pope kissing the ground of Poland on his first visit, he remarked that the world had changed in that moment.

After the lid came off and Solidarity was created, the USSR through their surrogates in the Bulgarian Secret Police[5] tried to stuff the genie back into the bottle and hired an experienced Turkish assassin, Mehmet Ali Ağca, who shot at the Pope four times in St. Peter’s Square in Rome, hitting him twice and severely wounding him. His wounds troubled his health for the rest of his life. Ağca was caught and sentenced in Italy then deported to Turkey where he was convicted of a previous assassination of a left- wing journalist.

Several years later the Pope visited and embraced Ağca in the Turkish prison as well as reaching out to his family and mother. He publicly and privately forgave Ağca, and a picture exists of Ağca kissing the ring of the Pope during the visit. In 2007, two years after the death of the Pope who had befriended him, Ağca converted to Roman Catholicism. Like the founder of his beloved Church, Jesus of Nazareth, Pope John Paul responded to violence, hatred, cruelty, and vengefulness with forgiving love. Every soul, every human being precious, unique, unrepeatable, capable of transformation. Even assassins.

There was little violence in the ‘revolution of conscience’ other than what the government perpetrated. Demonstrations. Protests. Courageous stands. Way too many ups and downs for a blog post.[6] See the footnote for a great video resource readily available. It took another decade until 1989 for free elections to finally finish off the regime.

To be sure many other factors contributed: the leadership in tandem with John Paul of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. The leadership of playwright Vaclav Havel in Czechoslovakia and Walesa in Poland and many others in Lithuania, Hungary, East Germany. But this was the Lord’s battle too and that of His shepherd, John Paul II, and it was definitive.

Between 1989 and 1990, they fell one by one. Poland first, then the rest: Czechoslovakia, Hungary, the infamous Berlin Wall came down in November of 1989. The guns of the Church had sounded, and the walls came down.

“Hope is a state of mind, not of the world. Hope, in this deep and powerful sense, is not the same as joy that things are going well, or willingness to invest in enterprises that are obviously heading for success, but rather an ability to work for something because it is good.” Vaclav Havel

[1] Unidentified photographer – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress‘s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID 2003678173. This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing.

Iosif Vissarionovich Stalin (1878-1953), leader of the Soviet Union between 1924 and 1953

[2] http://karnet.krakowculture.pl/en/18092-krakow-john-paul-ii-in-poland-photographs-by-chuck-fishman

[3] “Conscience is the most secret core and sanctuary of a man. There he is alone with God, Whose voice echoes in his depths. In a wonderful manner….” Gaudium et spes.

[4] Perhaps a tribute to Joseph Stalin. Stalin, his adopted name, is a derivation of the Russian for Steel.

[5] There is great controversy and much conflicting evidence supporting the claim that the USSR through the Bulgarians hired Mehmet Ali Ağca. But sufficient collaborative testimony and investigations lay the blame clearly at with the Communists. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attempted_assassination_of_Pope_John_Paul_II

[6] Great coverage of this in the 2018 documentary: “Liberating a Continent: John Paul II and the Fall of Communism” by Executive Produce Carl Anderson, former Grand Knight of the Knights of Columbus. Video clips in abundance and excerpts from Mr. Anderson, George Wiegel, definitive biographer of JPII, Reagan administration National Security Advisor, and many others. Streaming on Amazon Prime and other services. https://www.amazon.com/Liberating-Continent-John-Paul-Communism/dp/B01MS4VIGH

The red pumper bounced onto the driveway of the large ante bellum colonial with siren blaring. The house had once served as an inn, and currently was occupied by a half dozen mostly benign refugees from other late sixties communes. The flames fully engaged the structure and were seen through the windows. Everyone got out.

The red pumper bounced onto the driveway of the large ante bellum colonial with siren blaring. The house had once served as an inn, and currently was occupied by a half dozen mostly benign refugees from other late sixties communes. The flames fully engaged the structure and were seen through the windows. Everyone got out.

A “domestic disturbance” was treated like this: no police involvement because they were too far away to help. Bia, a recent resident, had moved into an apartment next to a small store front downtown, where she opened up a sheet metal artisan shop, welding and cutting small decorative pieces sold at craft fairs. Her boyfriend was an odd, slender, bearded, pony tailed archetype prone to buckskin jackets, cowboy hats, silver buckles and a 14” Bowie knife carried in a sheath on his belt. Bia’s daughter was my daughter’s age, and they became friends during the few months since Bia arrived in town. In January, our phone rang about eleven one weeknight, long after our bedtime. She called because we were one of the few she had gotten to know. The boyfriend, whose name fades, let’s call him Jim, was drinking, smoking dope and hitting her. Could I come down to help? Sure, I agreed, groggily.

A “domestic disturbance” was treated like this: no police involvement because they were too far away to help. Bia, a recent resident, had moved into an apartment next to a small store front downtown, where she opened up a sheet metal artisan shop, welding and cutting small decorative pieces sold at craft fairs. Her boyfriend was an odd, slender, bearded, pony tailed archetype prone to buckskin jackets, cowboy hats, silver buckles and a 14” Bowie knife carried in a sheath on his belt. Bia’s daughter was my daughter’s age, and they became friends during the few months since Bia arrived in town. In January, our phone rang about eleven one weeknight, long after our bedtime. She called because we were one of the few she had gotten to know. The boyfriend, whose name fades, let’s call him Jim, was drinking, smoking dope and hitting her. Could I come down to help? Sure, I agreed, groggily. steed, well actually, an F150. What could be better for a chainsaw guy than getting to play knight errant? On the way to her place, I practiced some tough threat lines involving emergency rooms, reconstructive dentistry and eating through a straw, all of which turned out quickly to be completely inadequate to the situation. The denouement was less than noteworthy. Jim had fled out the back door on the snow over the ice of Lake Minnehonk. I followed his tracks into the dark, axe handle in hand, and found him seventy yards out on the ice in a tee shirt disconsolately sitting and shivering in the snow, his knife still in its sheath. I asked him if he had a place to go. He said he did, in Waterville. I told him that’s where he would be staying. He started to cry. Bia packed a duffle bag into his dented Saab with Boulder County Colorado plates, and that was the last anyone ever saw of him. I went home to bed; Rita was glad to see me.

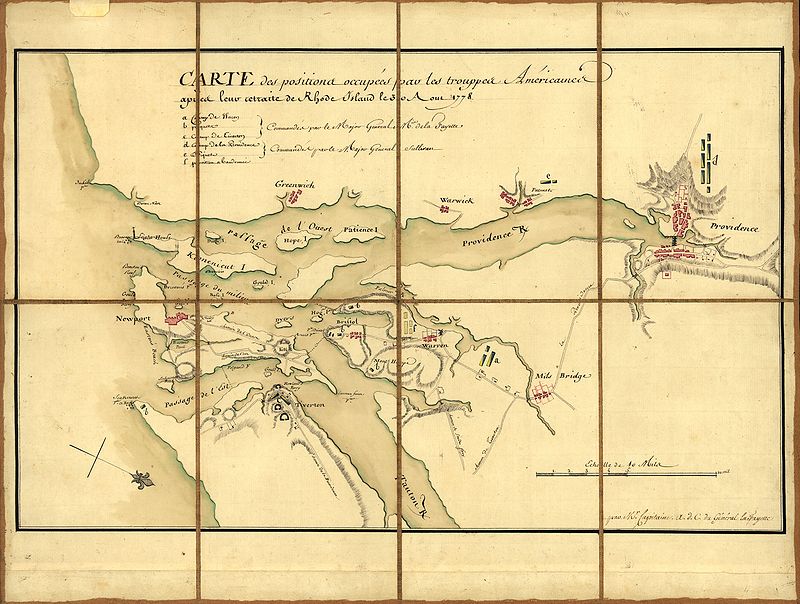

steed, well actually, an F150. What could be better for a chainsaw guy than getting to play knight errant? On the way to her place, I practiced some tough threat lines involving emergency rooms, reconstructive dentistry and eating through a straw, all of which turned out quickly to be completely inadequate to the situation. The denouement was less than noteworthy. Jim had fled out the back door on the snow over the ice of Lake Minnehonk. I followed his tracks into the dark, axe handle in hand, and found him seventy yards out on the ice in a tee shirt disconsolately sitting and shivering in the snow, his knife still in its sheath. I asked him if he had a place to go. He said he did, in Waterville. I told him that’s where he would be staying. He started to cry. Bia packed a duffle bag into his dented Saab with Boulder County Colorado plates, and that was the last anyone ever saw of him. I went home to bed; Rita was glad to see me. In the beginning, there were snowball fights after every storm, even though they presently are illegal in eight towns in Rhode Island, including nearby Newport and Jamestown. Not illegal here in Portsmouth, however, our town has a long history of dissent and rebellion against unjust laws and was founded in 1638 by Anne Hutchinson and others who wanted freedom from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Portsmouth was the site of the largest Revolutionary War

In the beginning, there were snowball fights after every storm, even though they presently are illegal in eight towns in Rhode Island, including nearby Newport and Jamestown. Not illegal here in Portsmouth, however, our town has a long history of dissent and rebellion against unjust laws and was founded in 1638 by Anne Hutchinson and others who wanted freedom from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Portsmouth was the site of the largest Revolutionary War A rainy December Saturday is the perfect time for reflection and to get a short Christmas letter together. We said last goodbyes to some good friends in 2021, three in the last two months. We’ll miss their company and just knowing they are there. We’ve joined in prayer for each that they have been welcomed home. “Well done, My good and faithful servant.” Each one was unique and precious and unrepeatable and irreplaceable. As we turn the corner into our fourth quarter century, this Christmas and end of year season, natural for reflection, has special poignancy.

A rainy December Saturday is the perfect time for reflection and to get a short Christmas letter together. We said last goodbyes to some good friends in 2021, three in the last two months. We’ll miss their company and just knowing they are there. We’ve joined in prayer for each that they have been welcomed home. “Well done, My good and faithful servant.” Each one was unique and precious and unrepeatable and irreplaceable. As we turn the corner into our fourth quarter century, this Christmas and end of year season, natural for reflection, has special poignancy. A local townsperson from forty or so years ago in Mount Vernon, Maine, taught in the English Department at the University of Maine. She grumbled to us once at one of her parties that the brilliant fall gold and red display of maples and birch and poplar was disturbingly garish, a vulgar excess that lures the tourists. The leaf peepers travel by the busload to northern New England and upstate New York each year to gawk and to raise the rates in the hotels and restaurants, filling the hospitality business gaps between the summer lakes splendor and the ski season. The leaf colors are enabled by the slow final ruin of the chlorophyll

A local townsperson from forty or so years ago in Mount Vernon, Maine, taught in the English Department at the University of Maine. She grumbled to us once at one of her parties that the brilliant fall gold and red display of maples and birch and poplar was disturbingly garish, a vulgar excess that lures the tourists. The leaf peepers travel by the busload to northern New England and upstate New York each year to gawk and to raise the rates in the hotels and restaurants, filling the hospitality business gaps between the summer lakes splendor and the ski season. The leaf colors are enabled by the slow final ruin of the chlorophyll  It has been written that the Holy Spirit is the Love proceeding from the Father and the Son within the Community of Love that is the Trinity of the Godhead. One of the key stories in the Christmas narratives occurs when Mary comes to help her also pregnant cousin after Mary began carrying the Christ child within her. In the presence of the baby Jesus, Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit; she was participating in the mysterious inner life of God. Human beings as their most noble calling possess the capacity to share in that inner life.

It has been written that the Holy Spirit is the Love proceeding from the Father and the Son within the Community of Love that is the Trinity of the Godhead. One of the key stories in the Christmas narratives occurs when Mary comes to help her also pregnant cousin after Mary began carrying the Christ child within her. In the presence of the baby Jesus, Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit; she was participating in the mysterious inner life of God. Human beings as their most noble calling possess the capacity to share in that inner life. None of us likely has the same degree or skill or eye, but the capacity for beauty exists by our nature. Imago Dei, in the Image of God, are undeserved gifts to us in our nature and our souls. The senses are there; the mind is there; the heart is there; the soul is there for all of us.

None of us likely has the same degree or skill or eye, but the capacity for beauty exists by our nature. Imago Dei, in the Image of God, are undeserved gifts to us in our nature and our souls. The senses are there; the mind is there; the heart is there; the soul is there for all of us. “One believes things because one has been conditioned to believe them.” Aldous Huxley, Brave New World

“One believes things because one has been conditioned to believe them.” Aldous Huxley, Brave New World How many of our stories start with “I met a guy?” Just as this one will. We were in the backyard of my daughter’s home in California earlier this spring during a birthday block party and cookout in the cul-de-sac out front for a neighbor turning ninety. One of their neighbors drifted in to see some of the yard improvements completed to adapt to the needs of two small active girls during a pandemic. Rodney’s daughter came as well, and the three girls ran helter-skelter testing the limits of swings, water tables, trapezes, trampolines, and slides. While the children joyfully yelped and played, we became acquainted in the way strangers sometimes do in unplanned encounters.

How many of our stories start with “I met a guy?” Just as this one will. We were in the backyard of my daughter’s home in California earlier this spring during a birthday block party and cookout in the cul-de-sac out front for a neighbor turning ninety. One of their neighbors drifted in to see some of the yard improvements completed to adapt to the needs of two small active girls during a pandemic. Rodney’s daughter came as well, and the three girls ran helter-skelter testing the limits of swings, water tables, trapezes, trampolines, and slides. While the children joyfully yelped and played, we became acquainted in the way strangers sometimes do in unplanned encounters.