“When the white owl flies, winter has found its voice.” Inuit saying

Sachuest Point Wildlife Refuge had another short visit from a snowy owl, the second such visit this winter. She had a two day layover in December at the refuge, was just passing through we think and has not been spotted since she was hanging around Island Rocks. She left before the paparazzi showed up. Snowy’s have a following, and when they grace us with an appearance the parking lot fills up.

Sachuest Point Wildlife Refuge had another short visit from a snowy owl, the second such visit this winter. She had a two day layover in December at the refuge, was just passing through we think and has not been spotted since she was hanging around Island Rocks. She left before the paparazzi showed up. Snowy’s have a following, and when they grace us with an appearance the parking lot fills up.

If they are on the roof of the visitor center as one was four years ago, the small lawn area in front of the main entrance is overrun with photography equipment worth more than my car. On tripods – lots of tripods sprouting like a field full of oil rigs with large telescoping lenses. A photographer and ornithologist told me one lens could cost fifteen thousand dollars.

We volunteer Friday afternoons in the Visitor Center. From December to February, at least a few visitors come to the hospitality desk each week to ask us where any snowy owls have been spotted with the excitement of a neighbor enthusing about the Pats back in the Super Bowl. Snowy owls are celebrities. Reports of a sighting on E Bird or Merlin are shared with online contagion as excitedly as if Taylor Swift was spotted at a Newport restaurant with her NFL star fiancé.

During the winter of 2022-23 a pair of snowy owls moved in for the season. The refuge had to close off the Price Neck Overlook Trail where they were nesting because too many hopeful observers were wandering off the trails to locate their nest, and they were stressing out the birds. Hard to get a parking spot, even with the overflow lot opened, so a snowy layover is a mixed blessing.

When they are hunting for lunch, it is major entertainment. A pair of barn owls were nesting on the refuge at the same time the snowys took up residence. Barn owls are not scarce globally but are considered rare and endangered in Rhode Island. Not as many barns for them as there once were. They became rarer still on Aquidneck Island after the snowy owls killed them both at the refuge. Another volunteer saw a barn owl grab a vole just before the snowy owl snatched up both the barn owl and its prey. Lunch and dessert. I would have loved to have seen that encounter.

“The snowy owl belongs to the great white silence of the Arctic, and when it comes south it brings that silence with it.” Bernd Heinrich, Winter World

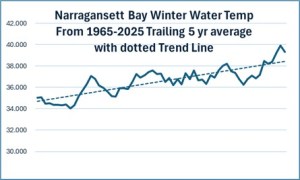

Visits by snowy owls used to be more common before the water warmed up in Narraganset Bay.[i] Our visitors were not fully mature, so they had mixed gray, black, and white feathers and not the purer white that earned them their name. Farther up north in the tundra if food becomes scarce, the snowy parents make a pragmatic decision when their hatched owlets grow larger and fledge. Time to get booted out of the nest and make their way south to find food. Ducks and barn owls beware. Darwin had some things right. Failure to launch is not an option.

Visits by snowy owls used to be more common before the water warmed up in Narraganset Bay.[i] Our visitors were not fully mature, so they had mixed gray, black, and white feathers and not the purer white that earned them their name. Farther up north in the tundra if food becomes scarce, the snowy parents make a pragmatic decision when their hatched owlets grow larger and fledge. Time to get booted out of the nest and make their way south to find food. Ducks and barn owls beware. Darwin had some things right. Failure to launch is not an option.

Because the bay waters are warmer and the winters are demonstrably less severe than in the days of my coming of age, the owls don’t have to come as far south to eat regularly. Thus, their visits are now less frequent.

It has not always been that way, not even counting the long era that lasted about eight millennia from twenty three to fourteen thousand years ago, when most of Rhode Island was under a mile deep glacier. That’s a long cold snap. Salty ocean water freezes when its temperature drops to 28 degrees, while freshwater freezes at 32. With billions of gallons of water Narragansett Bay takes a prolonged period of very cold weather to freeze over, especially as it is flushed twice every day with the tidal flows from the ocean.

We have enjoyed warming water for generations now, and especially so in the last fifty years. The winter surfers and the New Year’s Day polar plunge folks appreciate it. But this year is the exception to the trend and so far has been the coldest winter in thirty years. The ice we’re seeing now in some spots in the bay as shown in the satellite image is a rarity. Rhode Island needs to stay cold for a long while for Narragansett Bay to show ice. If warmth is lacking for long enough the bay can freeze solidly as it has frozen in the past, although we are unlikely to experience that again in our lifetime.

But this year is the exception to the trend and so far has been the coldest winter in thirty years. The ice we’re seeing now in some spots in the bay as shown in the satellite image is a rarity. Rhode Island needs to stay cold for a long while for Narragansett Bay to show ice. If warmth is lacking for long enough the bay can freeze solidly as it has frozen in the past, although we are unlikely to experience that again in our lifetime.

Beginning around the edges as an advancing gray slurry with the waves still undulating softly under it, the surface becomes ever more languid as if the sea is nodding off. Light and oxygen diminish under it as it solidifies, and the small inlets succumb to the proliferating crystals of ice. Torpor descends slowly below the ice as light and warmth fade. The fish and crustaceans slow their hunting and eat less; the metabolism of cold blooded species slows as the temperature drops in the water.

At Weaver Cove on our western Narragansett Bay shore a few hundred yards offshore this week we watched a raft of brants (a type of smaller goose). There were at least two hundred of them swimming together in a small area with no chop or waves – clear open water as still as a woodland pond. As if by prearranged signal, they rose as one and flew very fast towards Prudence Island. They are a resolute sign of defiance to the winter and refuse to go gentle into that good night.

According to then Deputy Governor William Greene, the winter of 1740-41 was “the coldest known in New England since the memory of man.” Except for a few days of warmer, rainy weather in mid-December while the General Assembly met in Newport, the deep cold was unabated. Perhaps then, like now, when the state legislature is in session, there is plenty of hot air. “Soon after this,” said Greene, “the weather was again so exceedingly cold that the Narragansett Bay was soon frozen over, and people passed and repassed from Providence to Newport on the ice, and from Newport to Bristol.”[ii]

“As cold as the winter of 1740-41 had been, the winter of 1779-80 was worse. From mid-December through mid-March, frigid Arctic air – accompanied by three major nor’easters – kept the temperature below zero for 11 consecutive days. Not only did the bay freeze, but according to some sources, much of Block Island Sound and the ocean beyond almost to the Gulf Stream was solid.”[iii] That was the winter that followed the killing weather of 1777-78, when George Washington and the remnants of the Continental Army were struggling to survive at Valley Forge.

In those times, sleds brought firewood to Aquidneck Island from the mainland because the British Army occupying Newport had cut down nearly every tree on the island for their campfires and the fireplaces in the homes their officers had occupied. Many residents whose families had been here over a century left. Newport never fully recovered as a major east coast port after the troops pulled out, leaving salted wells and scuttled ships to block the harbor. Sleds traversed the bay and people walked from Providence to Newport.

Cold is not a distinctive attribute as much as a lack of one. Like darkness is not a discrete quality, but a lack of light, so cold is a scarcity of the comfort of warmth. Nature has other analogies in our human self-inflicted winters. Vice is a poverty of virtue, corruption is a failure of renewal, death is an abandonment of life, indifference is a refusal of love, contempt a dearth of humility. Evil is a privation of good, not a Manichean battle of the Force v the Dark Side. Unlike the cold heart of winter which we suffer but can do little to change, virtue, renewal, joy and gratitude for our lives, love for one another, choosing the good, and humility are choices that are ours to make and live. In those choices, the ‘winter of our discontent’ is held at bay.

While we complain a bit about the cold, former Mainers like us quickly adapt, burn a little more wood in the stove, put together a hearty beef stew or a mood brightening lasagna, gather for church suppers in our parish and patiently wait for the spring and cherry blossoms that will soon emerge.

Barry Lopez wrote in Arctic Dream, “The white owl moves across the tundra like a drifting thought, as silent as snowfall.” New Englanders take what pleasure we can from the silence of the winter, persevere, bring in our wood from the shed, warm up some hot chocolate, take solace in reading by the stove, and wait. We wait. We’re good at it.

“Those who dwell among the beauties and mysteries of the earth are never alone or weary of life.” Rachel Carson, “Help Your Child to Wonder,” 1956 article in Women’s Home Companion

[i] The satellite image was posted by local TV station WJAR showing ice forming in Narragansett Bay in January of 2026. The upper bay section near Warwick shows a large frozen area. Floating ice fields can be seen floating just west of Prudence Island and a few other places. A prolonged cold snap has promulgated the ice, which we haven’t seen here for a while. Point of reference is the small foot like projection on the northeast end of Aquidneck Island. That is Sachuest Point where we have spent hundreds of happy hours.

The snowy owl photo was taken on the rocks at Sachuest Point in 2022 by me.

The chart showing the warming of Narragansett Bay was generated by a spreadsheet of five year increments from 1950 on from the University of Rhode Island Physical Data Master files showing the recorded temps and trend line.

[ii] From a 2014 article in the Jamestown Press, “When Narragansett Bay Freezes Over.”

[iii] Ibid

Cold. Penetrating deep cold, but exhilarating. On shore wind as the air rises over the still warmer land, and the ocean air rushes in to fill the vacuum. Cleansing. Lung filling. Soul filling. A sharp breeze comes over the water picking up moisture and is scrubbed as it comes. The air streams around and over Bluff and Stratton Islands in the harbor, loading up from beyond the horizon where the earth curves out of sight, past the Azores, past the edge of the world. Cold, clean, pure, merciless, but without bias or favor.

Cold. Penetrating deep cold, but exhilarating. On shore wind as the air rises over the still warmer land, and the ocean air rushes in to fill the vacuum. Cleansing. Lung filling. Soul filling. A sharp breeze comes over the water picking up moisture and is scrubbed as it comes. The air streams around and over Bluff and Stratton Islands in the harbor, loading up from beyond the horizon where the earth curves out of sight, past the Azores, past the edge of the world. Cold, clean, pure, merciless, but without bias or favor.