“We all want progress. But progress means getting nearer to the place where you want to be. And if you have taken a wrong turning then to go forward does not get you any nearer. If you are on the wrong road progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road and in that case the man who turns back soonest is the most progressive man.” C.S. Lewis, “The Case for Christianity”

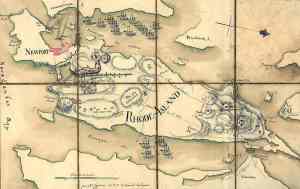

When we first moved to Aquidneck Island[i] in Narragansett Bay, a local carpenter working with me on home renovations told me he had not been off the island for ten years-he had everything he needed here, why waste his time going over bridges? Having lived in four states and traveled in at least forty others, I thought that was ridiculous. After seven years in this beautiful place, I gradually have become more empathic with his perspective. Indeed, why waste my finite time? However, we occasionally really do need to get to other places.

Absent a seaworthy boat or some flying lessons that leaves three avenues: the Mount Hope Bridge into Bristol, the Sakonnet River Bridge into Tiverton, and the Newport Pell Bridge into Jamestown. Our tiny state of Rhode Island is only thirty-seven miles wide and forty-eight miles long, but it has four hundred miles of seashore with its many inlets, islands, and bays small and large. Surrounded by the Tohu wa-bohu,[ii] bridges are not a trivial concern.

Late last year, Providence and all of Rhode Island suffered some of the worst traffic snarls in my memory when the cantilevered Washington Bridge on I 195 was first shut down and then severely restricted after a young engineer making a routine inspection discovered that one of its supports was rusting out, separating, and shifting each time a load hit it. Our forty-five-minute trip to Heritage Ballet with granddaughters became a dispiriting hour to an hour and a half without notice, and life changed around here. Only the diligence, then alarm, of a single engineer averted structural failure with dozens of cars dumped into the Providence River on the main access to the city from the southeast, and a terrible body count. Years of desultory inspections and shoddy practices led to the failure of a few large bolts and imminent collapse. Or was the original design with its vulnerability to a few bolts rusting out the underlying cause of the misery and potential tragedy?

Francis Scott Key Bridge Collapse James Rajda IStock

[iii]A few months later in March, a giant cargo ship lost power and the ability to turn in Baltimore Harbor and drifted at around 8 mph into one of the supports of the Francis Scott Key Bridge. Underlying that immediate cause was a faulty design concept that neglected to protect against an inadvertent collision.

I asked my friend ChatGPT about the power of a ninety-five-ton vessel loaded with an additional 4,700 twenty-foot ten-ton containers. It quickly came back with the calculations confirming the Dali struck one of the bridge’s supports with a kinetic energy impact of about 16.3 billion foot pounds. How would that compare to a fully loaded 18-wheeler at 80,000 pounds, I asked. Comparable, indeed, Chat told me, if the truck was travelling at 436 miles per hour. That would do it, I said. Chat agreed with its customary understated lack of humor. A major link to the city was destroyed, and the whole necessary commerce of the harbor was lost for months. Six men were killed who were maintaining the bridge. Some of the bodies were ever recovered. Only good fortune timed the collision to occur during the predawn and not when hundreds of commuters were crossing it.

Was the electrical fault cursing the Dali with a total loss of control the sole proximate cause of the crisis, or was the design and structure of the bridge built in 1977 the true source of the collapse? Federal standards were put in place in 1991 requiring fenders or “dolphins” be built to divert and protect bridge supports from errant giant cargo ships. Existing bridges were ‘grandfathered’ in. Only 34% of bridges in use over American navigable rivers and harbors under which commercial seagoing vessels travel every day protect the structural supports that hold them up.

The Newport Pell Bridge, which is the heavily travelled only bridge on the south end of our island with access to Route 95 south to New York and beyond, is one of them, and of a similar design to the now destroyed Francis Scott Key Bridge. Every day we see the large container ships, tankers, and cruise ships in Newport navigating under the bridge.

There are far more critical bridges than those spanning rivers. Some connect us along more profound ways. Or don’t. We can look at how they are supported and how the supports are holding up.

“If you see somebody, would you send ’em over my way?

I could use some help here with a can of pork and beans.” John Prine, “Knockin’ on Your Screen Door.

Slowly, inexorably, the unkempt premises of our youth develop into how we think, and the murky waters of the fishbowl in which we swim limits what we see. What we know. What we think we know. Our assumptions about what is real. C.S. Lewis once wrote, “The future is something which everyone reaches at the rate of sixty minutes an hour, whatever he does, whoever he is.” Thus, it is for us all, and it is beneficial for all to squint through the walls of the bowl from time to time.

Recent polls confirm that 25% of voters hate and distrust both major candidates in this year’s elections, the highest “double hater” rate in forty years. How ever did we come to this? What divides us is embedded more deeply than two unlikeable politicians. And far less amenable to a quick fix or the next election or better candidates.

MAGA vs wokeism in our hardened silos. Both sides regularly post memes of their opposition depicted as ignorant, compliant sheep. Can we all be ruminating, cud chewing, herbivores in adjoining pastures suffering through a drought? Maybe.

Both the MAGA true believers and the woke minions arose from the assumptions and ideas of Enlightenment philosophers and classical liberalism. The same soil raised both grain and weeds, with the weeds stipulated by the other side. When the liberal ideology of democracy, individualism, and liberty seemingly triumphed over the other more baleful ‘isms’ of the twentieth century, our assumptions and premises hardened. We determined that liberalism[iv] and liberal democracy were not only the most just expression of government and philosophy yet devised by human beings, but the only just one, the ultimate end of progress, what we all should and must aspire to. Coloring outside those lines is unrealistic and traitorous. The water in our fishbowl. To think otherwise is to question our most fundamental assumptions.

Consider that both MAGA advocates and the wokeism cancel culture may seem like the basic divide in our culture but have both arisen from the same premises. The definition of the terms of those premises have rusted out from when they were conceived. Liberty and individualism as the basis of human happiness have evolved, moved on, remade themselves predetermined by their headwaters.

Happiness is no longer understood in the context of the preliberal Aristotelian concept of discovering and learning an objective and common goodness and virtue, then living our lives congruent with that. The closer we get to the ideal, the happier we are due to our unchangeable nature. No, happiness has become the unfettered freedom to do what we want to do, our emotional and ephemeral and shifting desires.

Liberty has ceased to be the freedom to do what we ought. “Ought” is no longer a broadly accepted concept – what C.S. Lewis named the “Tao,” the vestigial collective conscience of commonly held beliefs about the good, the true, and the beautiful: what it means to be good wired into our nature. No, liberty has devolved into the absolute freedom to do what we want, when we want – with the one provision that we don’t harm anyone else. What quickly is exposed as a fantasy of impossible harmlessness is fated to be a perpetual struggle of conflicting wills, leaving us atomized and alone, bewildered and hostile. Without a common ground of what we should be, how do we negotiate a just solution? Or any solutions?

The leftward interpretation of that new definition of freedom tends to be limited to all things pleasurable, especially relating to sexual expression and to avoidance of pain. For those on the right, while paying minimal homage to something called “family values,” the new understanding of freedom tends toward all things economic and unrestricted capitalism resulting in ever more disparity between those that got it, and those that don’t. Freedom means financial freedom. But left and right are merely different interpretations of where classical liberalism led us.

The philosophical supports of liberal democracy and classical liberalism have rusted out from the vulner-abilities of their model. The fenders and dolphins that would protect them have been neglected. Or forgotten entirely.

“When he woke she was leaning against his shoulder. He thought she was asleep but she was looking out the plane window. We can do whatever we want, she said.

No, he said. We can’t.” Cormac McCarthy, “The Passenger”

The authors of our Declaration of Independence and Constitution understood that the sustainability of our whole project of a democratic republic would succeed or fail on the common beliefs and shared values of its citizens, and if those shared values evanesced, it would collapse.[v] Yet, those common beliefs and shared values are not passed along by government; they are learned in organized or informal associations, churches, and most importantly in families. Passed down in a thousand conversations and experiences one person at a time. All of these fenders and protections of associations, faith, and family have degraded in an accelerated fashion over our lifetimes due to the same foundational principles of individualism, materialism, and the primacy of will.

The evidence of that change is all around us and was exposed clearly in a 2023 Wall Street Journal poll that compared the highest values of our citizenry in 1998 and where they shifted in twenty five years. To recap the key findings:

Patriotism: The importance of patriotism has decreased significantly, with only 38% of respondents in 2023 considering it very important, down from 70% in 1998.

Religion: The value placed on religion has also diminished, with 39% of respondents in 2023 viewing it as very important, compared to 62% in 1998.

Community Involvement: The significance of community involvement fell dramatically, with only 27% considering it very important in 2023, compared to 47% in 1998.

Having Children: The importance of having children dropped from 59% in 1998 to 30% in 2023. That is reflected in a birth rate well below replacement, a potential demographic winter, a still prevalent popular misbelief of overpopulation, and the difficulty of funding the social safety net of things like social security and Medicare because of an aging population and not enough workers contributing to keep them solvent.

The family is in such a crisis that over 50% of kids are raised by single parents or unmarried parents with the least affluent and educated among us suffering the most loss. Having children should be seen as an indicator of hope and confidence in the future. No kids indicates a debilitating skepticism about where we are headed.

Money: Conversely, the importance of money increased from 31% in 1998 to 43% in 2023. When hope is lost, financial security is perceived as more important.

The sacrifice and common vision of the founders of our country have given away to subjective and fungible aspirations that find little reason to cohere, and many reasons to pursue their own indulgence.

“Read not to contradict and confute, nor to believe and take for granted….but to weigh and consider.”

Francis Bacon[vi]

Six years ago, Dr. Patrick Deneen, political philosopher and political science professor at Notre Dame, published a book of powerful and disturbing insight, “Why Liberalism Failed.” It has been positively and thoughtfully reviewed by such diverse thinkers as Barack Obama and Rod Dreher as ideas well worth considering. He pleased and distressed readers from both sides of the aisle, sometimes both in the same reader. A great debate ensued across many platforms. Summarizing it in a blog post is nigh on impossible, but for this some relevant points give us plenty to think about.

To summarize the many ideas worth your attention, a reductionist, and inadequate summary of complex ideas follows below. Much better if it tempts you into buying the book or taking a trip to the library. The footnotes in this post that contain quotes that are worth your scrutiny. Better yet, read the book and some of the abundant commentary with a quick search.

Patrick Deneen critically examined the liberal political philosophy that has dominated Western societies for centuries. Deneen argues that liberalism, both in its classical and progressive forms, is inherently flawed and has led to many of the social, political, and economic crises we face today.

Liberalism contains internal contradictions that make it unsustainable in the long run. While it promotes individual freedom, that same perceived freedom simultaneously undermines the communal bonds and social structures necessary for maintaining that freedom. The emphasis on individual autonomy and rights has eroded traditional communities and institutions. This has led to social fragmentation, weakening the societal fabric that supports a functioning democracy.

Liberalism’s promotion of market-based economies has resulted in significant economic disparities. The focus on individual success has led to a concentration of wealth and power, exacerbating social inequalities. The liberal pursuit of endless economic growth and consumption also has contributed to environmental degradation. The prioritization of human dominion over nature has led to ecological crises that threaten the planet.

Liberalism’s emphasis on personal choice and freedom has led to political polarization and a breakdown in civil discourse. The lack of a shared moral framework has complicated attempts to address collective challenges effectively, leading to many impasses, obstructing civil discourse, and mutual understanding across ideological lines. We have busily been building our own tower of Babel for decades.

Does anyone doubt that is the situation we find ourselves in?

The liberal embrace of technological advancement, without sufficient ethical thinking, has resulted in technology dominating human life. We face concerns about privacy, autonomy, and the role of technology in shaping human values.

And most troubling of all, the focus on individualism has led to a loss of shared purpose and meaning. As traditional sources of identity and community have weakened, people have struggled to find a sense of belonging. Deneen calls for a rethinking of political philosophy that goes beyond liberalism. He advocates for a return to more localized, community-oriented ways of life that prioritize human relationships, ethical considerations, and environmental stewardship.

Deneen’s book argues that the very principles that undergird liberalism have sown the seeds of its failure, leading to widespread social, economic, and environmental issues. He urges a reconsideration of our political and social structures to foster a more sustainable and cohesive society. A longer quote from the book is included in the footnotes and expands the basic concepts of the book.[vii] I recommend them to you.

“Perhaps above all, liberalism has drawn down on a preliberal inheritance and resources that at once sustained liberalism but which it cannot replenish. The loosening of social bonds in nearly every aspect of life—familial, neighborly, communal, religious, even national—reflects the advancing logic of liberalism and is the source of its deepest instability. …. Liberalism has failed—not because it fell short, but because it was true to itself.” Patrick Deneen, “Why Liberalism Failed”

We drive over our sagging bridges without hesitation or any concern that they may collapse into the water. Roman culture lasted for well over a thousand years, and her citizenry had little cause to think it wouldn’t last for another thousand. Her citizens had no fears that it would crumble under its own internal contradictions, flaws, hedonism, complacency, and hubris. But collapse it did. There are lessons there.

The ideas to think about here are that perhaps the central supports of liberalism have rusted out since the founding of the American republic. Reflecting on that potential for collapse under its own weight, what adjustments or profound changes need to be thought about as we move into the twenty first century after its first twenty five years. Changes in society; changes in our local support social groups; changes in ourselves.

Changes that may fall upon us whether we are prepared to understand or deal with them. Like the gravity against which bridges struggle to withstand, they have their own inevitability.[viii]

“The truth is like a lion; you don’t have to defend it. Let it loose; it will defend itself.” St. Augustine

[i] Aquidneck Island consists of the original settlements of Portsmouth, where we live. It was founded in 1638, and Newport was founded in 1639 to our south. After many territorial disputes between the busy port city of Newport and more rural Portsmouth, a permanent resolution was agreed upon by founding the appropriately named Middletown in 1743. The island is only five miles wide and fifteen long, but sometimes it’s just hard to get along. Separate governments still exist for all three – two towns and a small city of long distinction.

[ii] The Tohu wa-bohu is the ancient Hebrew term for the sea and symbol of the formless and terrifying emptiness and confusion, the chaos without God before He formed the earth. When Jesus calmed the sea for the terrified disciples in the New Testament, it told of both a literal event and a symbol for God’s power and providence.

[iii] Image copyright from IStock and photographer James Rajda with permission

[iv] In this context, liberalism refers to classical liberalism as expressed by John Locke, not liberalism as restricted to the progressivism it connotes for the most part in contemporary understanding.

[v] Founding Fathers and the Concept of Virtue:

John Adams famously wrote, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious People. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other”. He believed that the success of the American republic depended on the virtue of its citizens.

Thomas Jefferson also emphasized the importance of education and the cultivation of virtue. He believed that an informed and virtuous citizenry was essential for the functioning of a democratic society. He was a Deist, not a Christian like Adams, but he believed that natural rights were given by God, however he defined that, and not subject to denial by men or law: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

James Madison acknowledged the need for checks and balances within government to mitigate the effects of human frailty but also stressed the importance of civic virtue.

Thus, citizens being formed in the virtues like prudence, self-sacrifice even to giving their lives and fortunes, temperance, right judgment, and a commonly held understanding of objective good were essential to the sustainability of a democratic society.

[vi] Saw this quote posted by a dear friend, Father Joe McKenna. Francis Bacon is considered the inventor of the scientific method.

[vii] Some quotes from the book, “Why Liberalism Failed:”

“A main result of the widespread view that liberalism’s triumph is complete and uncontested—indeed, that rival claims are no longer regarded as worthy of consideration—is a conclusion within the liberal order that various ills that infect the body politic as well as the civil and private spheres are either remnants of insufficiently realized liberalism or happenstance problems that are subject to policy or technological fix within the liberal horizon. Liberalism’s own success makes it difficult to sustain reflection on the likelihood that the greatest current threat to liberalism lies not outside and beyond liberalism but within it. The potency of this threat arises from the fundamental nature of liberalism, from what are thought to be its very strengths—especially its faith in its ability of self-correction and its belief in progress and continual improvement—which make it largely impervious to discerning its deepest weaknesses and even self-inflicted decline. No matter our contemporary malady, there is no challenge that can’t be fixed by a more perfect application of liberal solutions.

These maladies include the corrosive social and civic effects of self-interest—a disease that arises from the cure of overcoming the ancient reliance upon virtue. Not only is this malady increasingly manifest in all social interactions and institutions, but it infiltrates liberal politics. Undermining any appeal to common good, it induces a zero-sum mentality that becomes nationalized polarization for a citizenry that is increasingly driven by private and largely material concerns. Similarly, the “cure” by which individuals could be liberated from authoritative cultures generates social anomie that requires expansion of legal redress, police proscriptions, and expanded surveillance. For instance, because social norms and decencies have deteriorated and an emphasis on character was rejected as paternalistic and oppressive, a growing number of the nation’s school districts now deploy surveillance cameras in schools, anonymous oversight triggering post-facto punishment. The cure of human mastery of nature is producing consequences that suggest such mastery is at best temporary and finally illusory: ecological costs of burning of fossil fuels, limits of unlimited application of antibiotics, political fallout from displacement of workforce by technology, and so forth. Among the greatest challenges facing humanity is the ability to survive progress.

Perhaps above all, liberalism has drawn down on a preliberal inheritance and resources that at once sustained liberalism but which it cannot replenish. The loosening of social bonds in nearly every aspect of life—familial, neighborly, communal, religious, even national—reflects the advancing logic of liberalism and is the source of its deepest instability. The increased focus upon, and intensifying political battles over the role of centralized national and even international governments is at once the consequence of liberalism’s move toward homogenization and one of the indications of its fragility.”

[viii] I enthusiastically recommend a more recent Substack post by N.C. Lyons on a different aspect of the same issues.

“Autonomy and the Automaton” Here’s a quote to get your attention:

“The paradox is this: we subsist under an increasingly totalizing and oppressive managerial regime, in which a vast impersonal hive-mind of officious bureaucrats and ideological programmers aims to surveil, constrain, and manage every aspect of our lives, from our behavior to our associations and even our language and beliefs. This rule-by-scowling-HR manager could hardly feel more collectivist – we’re trapped in a “longhouse” ruled over by controlling, emasculating, spirit-sapping, safety-obsessed nannies. Naturally, our instinct is to sound a barbaric yawp of revolt in favor of unrestrained individual freedom. And yet, as I’ve endeavored to explain several times before, it is also a kind of blind lust for unrestrained individualism that got us stuck here in the first place.

The paradox is that the more individuals are liberated from the restraints imposed on them by others (e.g. relational bonds, communal duties, morals and norms) and by themselves (moral conscience and self-discipline), the more directionless and atomized they become; and the more atomized they become, the more vulnerable and reliant they are on the safety offered by some greater collective. Alone in his “independence,” the individual finds himself dependent on a larger power to protect his safety and the equality of his proliferating “rights” (desires) from the impositions of others, and today it is the state that answers this demand. Yet the more the state protects his right to consume and “be himself” without restraint, the less independently capable and differentiated he becomes, even as his private affairs increasingly become the business of the expanding state.”

If we had lived in the Roman Empire, which lasted about 500 years as the Western Roman Empire and another thousand or so as the Byzantine Empire based in Constantinople, we would have expected that daily life probably would never change

If we had lived in the Roman Empire, which lasted about 500 years as the Western Roman Empire and another thousand or so as the Byzantine Empire based in Constantinople, we would have expected that daily life probably would never change

A friend told us recently about this meme on Facebook with a simple picture of an egg and the caption, “In Alabama, this is a chicken.”

A friend told us recently about this meme on Facebook with a simple picture of an egg and the caption, “In Alabama, this is a chicken.” and answered by the science of embryology. Advancing technology has provided another compelling proof, the visual, emotional confirmation of ultrasound images, which have in many ways changed the discussion. No one ever looked at the live images of a developing human being in their womb and thought, “This is a fetus made up of ‘meat Legos’** or an undifferentiated clump of tissue with which (because I have the power), I can do anything I want.” No, no – they put the images up on their refrigerator with magnets in wonder and joy. This is my baby.

and answered by the science of embryology. Advancing technology has provided another compelling proof, the visual, emotional confirmation of ultrasound images, which have in many ways changed the discussion. No one ever looked at the live images of a developing human being in their womb and thought, “This is a fetus made up of ‘meat Legos’** or an undifferentiated clump of tissue with which (because I have the power), I can do anything I want.” No, no – they put the images up on their refrigerator with magnets in wonder and joy. This is my baby. humans are female. One half are male. Science informs us in the instant a human sperm enters a human egg, there is a flash of light, and in 2016, a lab in Northwestern University filmed it, something to do with the zinc released from the egg.

humans are female. One half are male. Science informs us in the instant a human sperm enters a human egg, there is a flash of light, and in 2016, a lab in Northwestern University filmed it, something to do with the zinc released from the egg. Rita and I will often walk Sachuest Beach. Sometimes we sit at Surfer End and pray or watch the surfers or the waves on a smaller wave day. We have been transfixed watching them build with the wind far out into the bay. As they approach the shore, the larger ones will break twice: once about fifty feet out and a second time when gravity again overcomes momentum and the top curls over very near shore.

Rita and I will often walk Sachuest Beach. Sometimes we sit at Surfer End and pray or watch the surfers or the waves on a smaller wave day. We have been transfixed watching them build with the wind far out into the bay. As they approach the shore, the larger ones will break twice: once about fifty feet out and a second time when gravity again overcomes momentum and the top curls over very near shore.